Size Matters

Intro

Before building protocols (Anoma and Namada), I deanonymized blockchains. My first job in crypto was at Chainalysis, who helped US Government agencies seize +1B in cryptocurrency in 2020 and law enforcement recover $30M from the Ronin Bridge hack in 2022. I joined as a data scientist between 2017 and 2018 and this experience made it very clear to me that protecting user data is paramount – especially if we want decentralized protocols to replace the financial system and serve as alternatives to exploitative paradigms.

Ever since, the usage of ZKPs and other cryptographic schemes has proliferated and we see more and more outstanding cryptographers involved in bringing data protection to blockchains.

After so many years, I noticed that the vast majority in the blockchain space know that data protection tech sucks. But very few know – why – it sucks.

This extends to cryptographers, as I also found out that being an outstanding cryptographer doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re an outstanding data protection tech builder. Unless you’re only building for cypherpunks. IMO Cypherpunks don’t have problems with data protection, because even if the tech sucks, they know how to get around its limitations.

But I’m building shielded tech for everyone, not just for cypherpunks.

My chain analyst’s POV has helped me clearly articulate where data can be leaked, how the tech can go wrong, and what to prioritize while we build Namada as a product that brings the best practical guarantees to users today.

I hope this helps you too, if you’re also building data-protecting protocols and dApps.

Acknowledgements

Cheers to Mary Maller, ceteris, zooko, Mikerah, Can, Joe, Christopher, and D for taking the time to read this article and giving me lots of feedback :3

Thinking like a chain analyst

When data scientists / analysts discovered blockchains, they probably felt like California farmers when they discovered gold. It’s not just that all the data is publicly available, but also that there are full nodes that provide you the data for free and tons of tools and APIs that they can use to get the data they want and how they want it. Combined with a growing number of open-source analysis tools, it is very cheap and easy for anyone to become a chain analyst.

Most people think that chain analysts are detectives. They’re not. This distinction matters because it changes what you’re defending your users from.

Bob is a detective, and his job is to catch the culprit, one individual or a smaller group, and (good) detectives need to be certain that whoever they caught is in fact the culprit. In other words, detectives need 100% confidence that their conclusion is right and who specifically the culprit is.

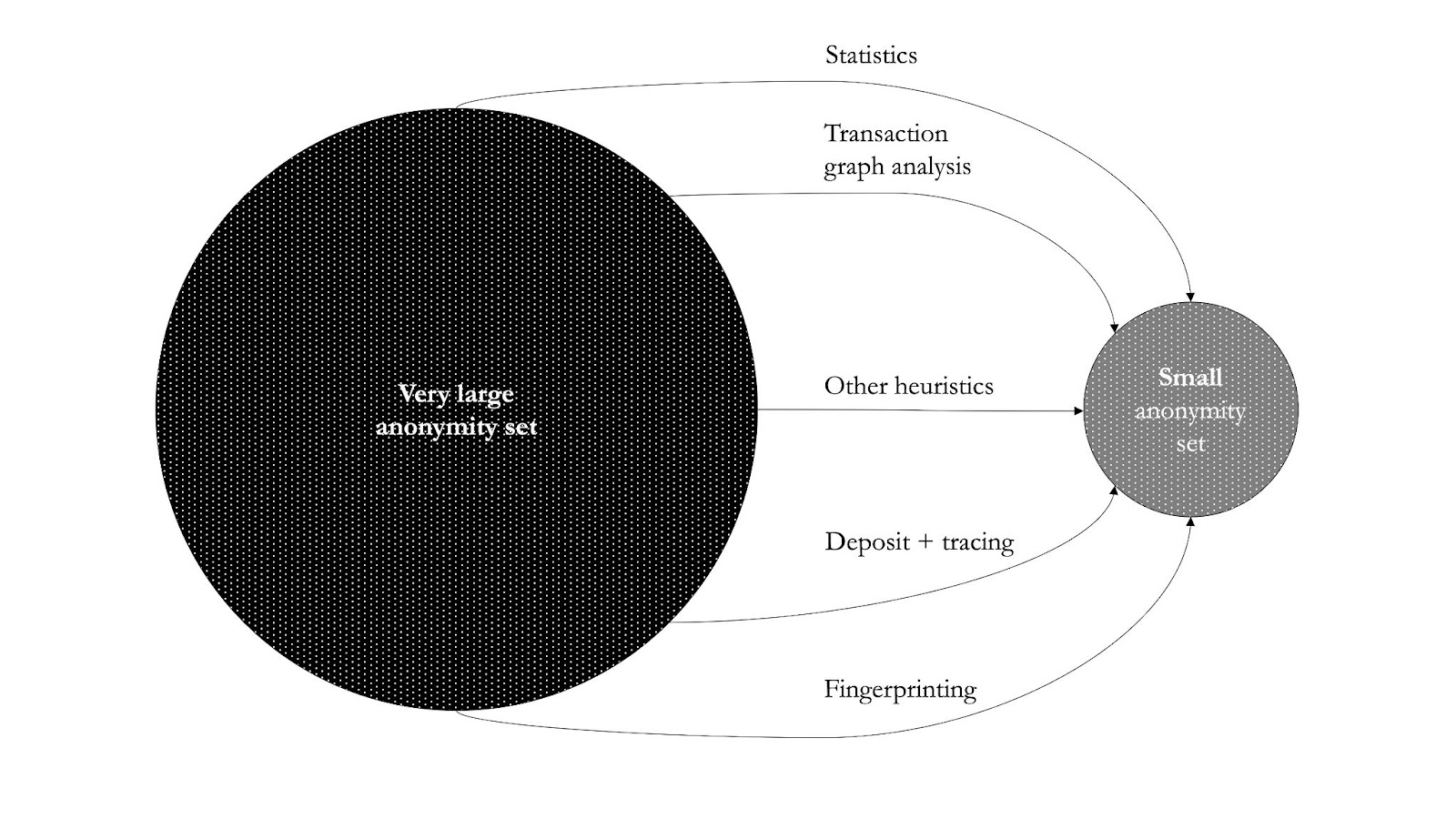

Chain analysts like Awa are completely different, they have one job: turn a very large dataset into a very small dataset. Usually, with the end goal of reducing the anonymity set (aka deanonymizing) and/or to classify what they’re doing on a network (aka clustering).

Unlike detectives, chain analysts strive for the highest accuracy when they can, but in most cases they will settle for a confidence level << 100%. They care a lot less about specifics, such as real-world identity and compete with each other on how much coverage they’ve got on a network. For example, whoever covers 75% of all addresses Bitcoin is better than another one who can only cover 50%.

Of course, the success metrics of a chain analyst are not binary, and can vary depending on what and whom the analysis is for.

Some chain analysts do it for fun, others for science, but most do it for profit.

Chain analysts get paid – a lot of – money for helping others make more money (providing market insights for investors and traders), to ensure that whoever should’ve paid the taxes has done so (compliance), or to make the lives of people who employ Bob easier (law enforcement, investigations).

Depending on who your customer is, you might focus more on higher confidence, more coverage, more granular clusters or specific clusters, and so on.

Working as a chain analyst

But ok, what does a chain analyst do? I summarized this into a few diagrams.

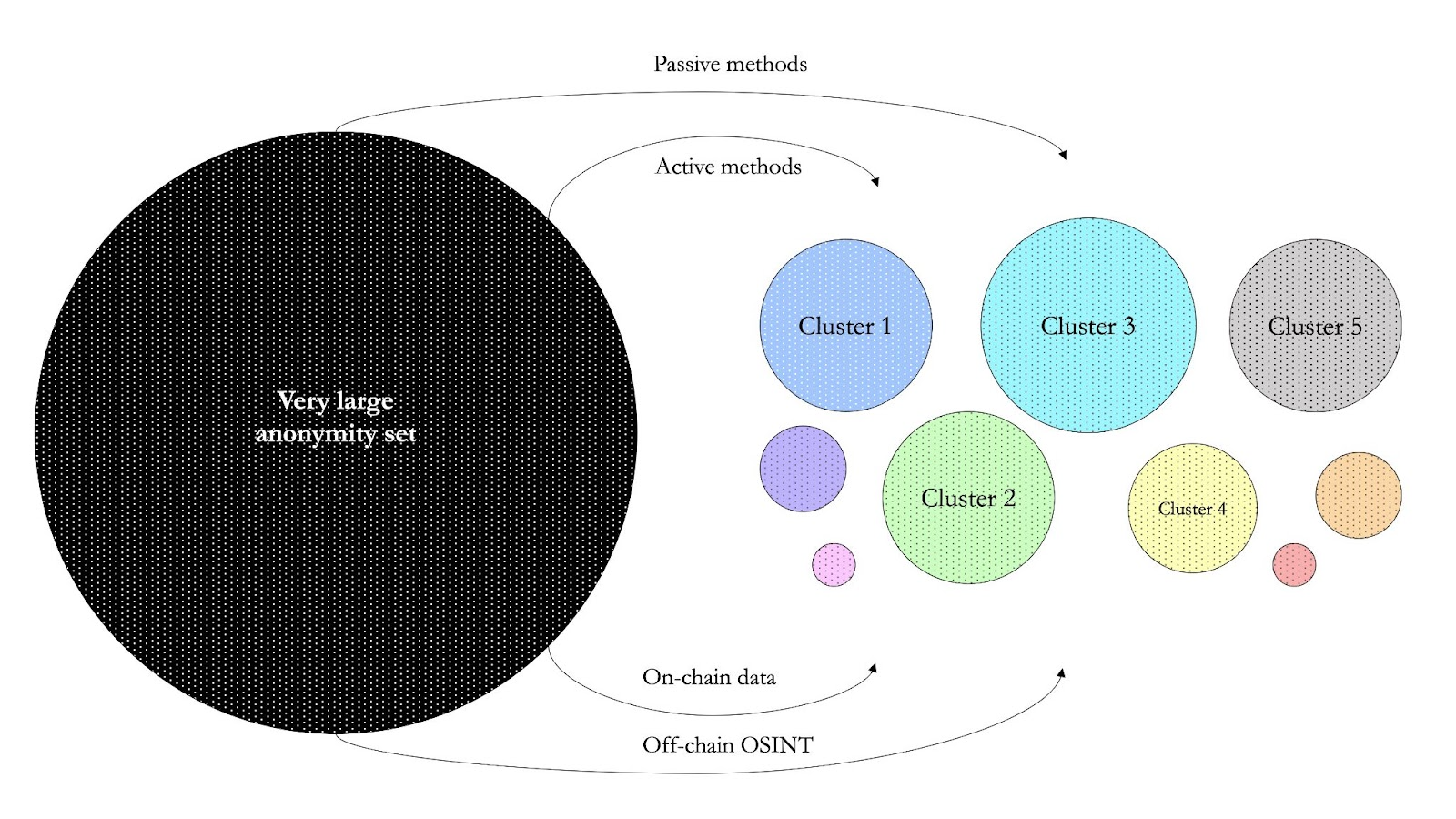

You start with a very large dataset (e.g. say all addresses on Bitcoin). Then you apply different methods to reduce the size of this set to a smaller one. I group the methods into two: passive and active methods.

Passive vs. active methods

Passive methods include statistics, heuristics, timing, value, and fee analysis. It sounds very sophisticated, but they’re not, you can do them at home with the most basic Python libraries. Since transparent blockchains reveal the entire transaction graph, chain analysts' results can be crazy good by just applying basic statistics.

For reference, a paper published in 2022 (Tang et al.) measured that while the size of the anonymity set was of 44,014 transactions across all values (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 ETH), the practical anonymity set is of 16,661 – which is 62.46% smaller than what users would expect – the study only used passive methods.

Unlike with passive methods, where you’re just observing what’s going on in a network, in active methods you’re directly interacting with a blockchain trying to find data that you cannot get using passive methods. Active methods are pretty cool. It’s like chain analysts vs. transparent blockchains at its finest, because truly decentralized blockchains are not able to discriminate against who uses them – which is how blockchains should be – including chain analysts.

Some active methods are quite simple, for instance, depositing funds to the addresses provided by custodial services like exchanges. Say you make a deposit to your Coinbase address. From one deposit, you can get the following data: first, this address is a Coinbase address; second if Coinbase doesn’t use unique addresses per customer, you get to see all historical deposits from other Coinbase users; third, if you’re lucky, you get to see Coinbase moving the funds around to other internal addresses – much data, very wow.

Other active methods are more sophisticated. My favorite one is the Danaan-gift attack and here’s how it works.

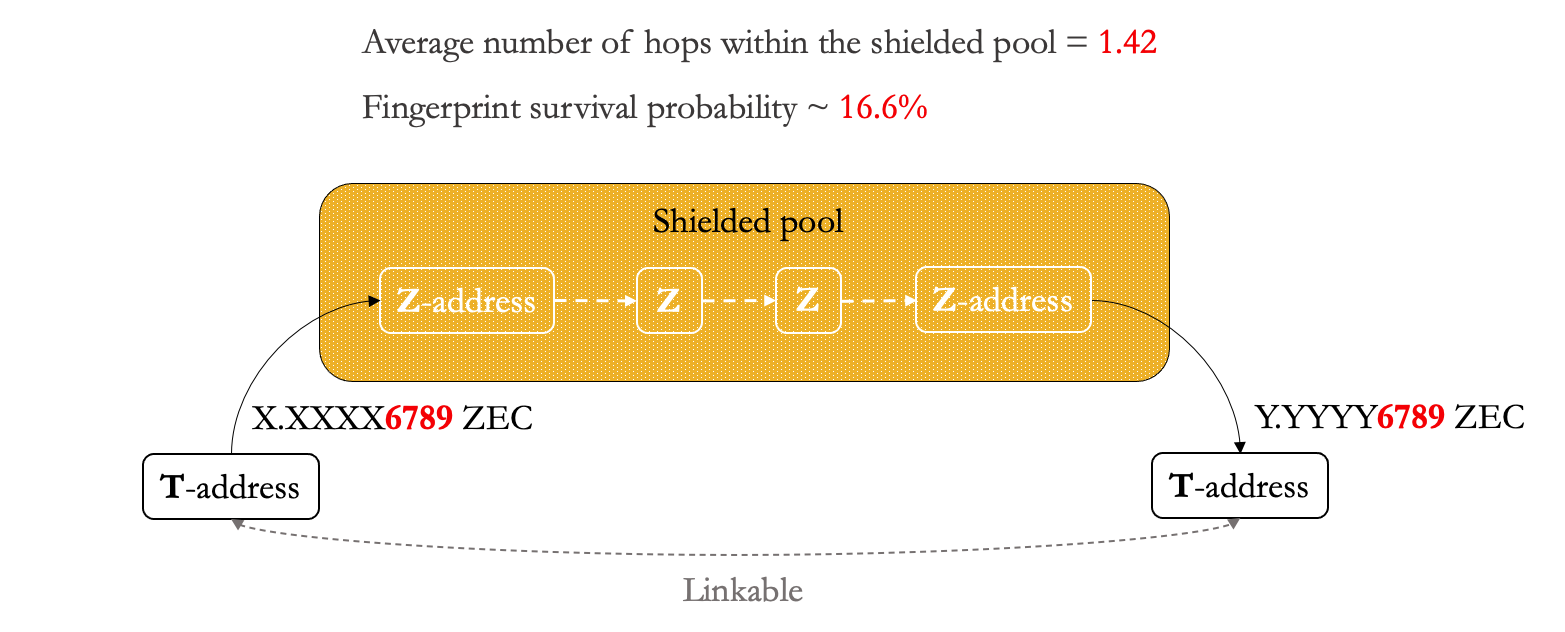

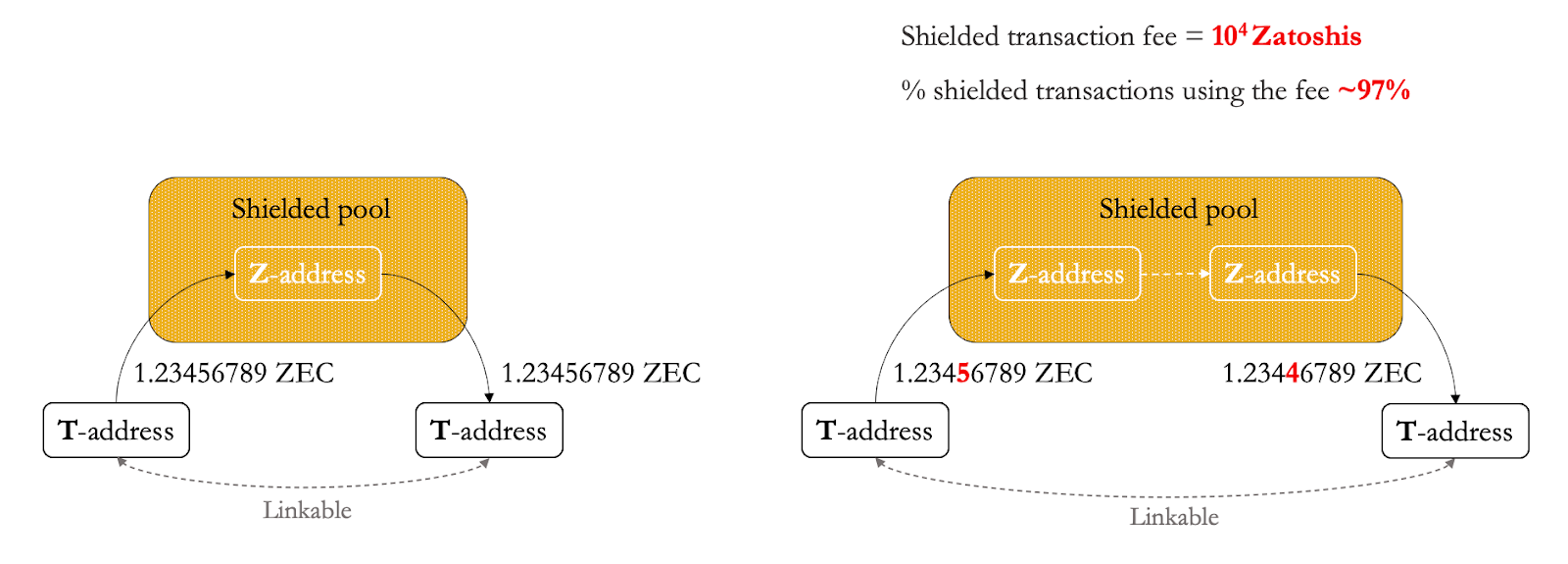

Most users specify transfer amounts’ integers and up to one to four decimal numbers, right? In a Danaan-gift attack, the attacker’s goal is to leave a fingerprint on the unsuspecting user by sending a very small amount of funds (dust) but with a unique sequence of lower decimals. This can be very useful if you want to link transparent addresses going in and out of a shielded pool like on Zcash or on Aztec’s ZK Money. This way, even if you cannot see what happens within the shielded set, you can link the fingerprinted withdrawal addresses and correlate them with the deposit addresses.

While fingerprint survivability on Zcash was about 16.6% (Biryukov et al), a paper published in 2020 (Béres et al.) observed that the lower the number of transactions of a user, the higher the fingerprint survivability. For example, on a Zcash-like application deployed on Ethereum (e.g. Aztec), the fingerprint survival probability is about 21.83% when an address only sent 50 transactions. The higher the survival rate, the more transactions in and out of a shielded pool can be deanonymized by a chain analyst.

On-chain vs. off-chain data

Until now, we’ve only used on-chain data. Things get even more fun as soon as you add off-chain data.

Think of off-chain data as a subset of Open Source Intelligence (OSINT). Most chain analysts use what’s available on the internet, including: websites, forums, social media, and so on. They’ve been doing this way before Twitter became popular among crypto degens. In the early Bitcoin days, users often posted their addresses in public forums or transaction hashes on reddit. Chain analysts crawled all this data and mapped them to on-chain data.

Another goal as a chain analyst is to cluster. The goal is to turn the large dataset into multiple smaller clusters.

The most common clustering practices group addresses on a blockchain based on what they’re doing. For example: the cyan cluster below could be exchanges, the green cluster could represent stores or services that accept Bitcoin as a form of payment, and the yellow cluster could represent mixing services.

For clustering, chain analysts can apply a combination of passive and active techniques, and on- and off-chain data. The ultimate wombo combo is when a chain analyst combines all the above with data from side channels, analysis of the p2p networks or mapping IP addresses.

A fun fact is that clustering, as in labeling the subsets by activity, used to be harder when there were only Bitcoin and bitcoin-like blockchains, since all you can on these networks is UTXO-based transactions.

With Ethereum and the growth of Ethereum-like blockchains with an account model and smart contracts, clustering has become trivial: a chain analyst doesn’t even have come up with a label, since you can just look at the logic of the smart contracts of every dApp to figure out what they do.

Combine it with ENS domains, crypto-enabled social media (e.g. Gitcoin, 3Box, or HumanityDAO), NFTs as twitter profiles among other fads that lead to collective doxxing… Ethereum’s basically stealing the jobs from chain analysts.

Shielded transactions vs. chain analysts

FYI here I use the word ZKPs to refer to zk-snarks. IMO zk-snarks are technically superior to ring signatures, TEEs, etc, so I left the rest out of scope. Depending on the interest, I might write a separate article that explains the differences among these schemes in privacy guarantees for users. Meanwhile I can really recommend watching the talk Satoshi Has No Clothes by Ian Miers.

First, ZKPs != data protection

You can deploy ZKPs to achieve different properties, such as succinctness in data or efficient verification. And you can deploy ZKPs for data protection, but it doesn’t provide practical guarantees for your users. You might’ve noticed in the previous section that very similar techniques used to deanonymize and cluster pseudonymous blockchains can get very good results on blockchains that use ZKPs.

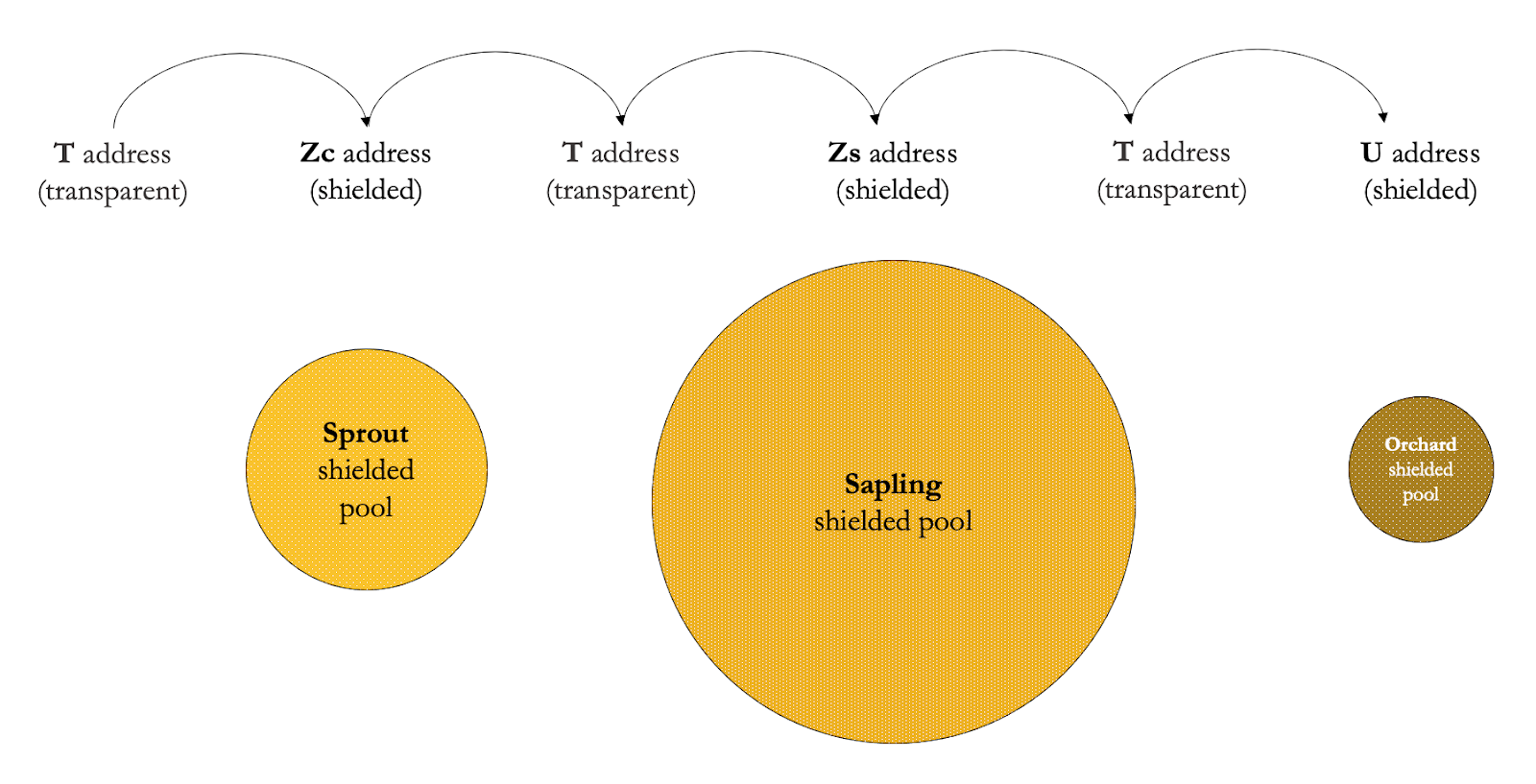

To understand where things can go wrong, we first need to understand how a shielded pool works. The best starting point for this is Zcash, a fork of Bitcoin that supports transparent transactions and that uses zk-snarks for shielded transactions.

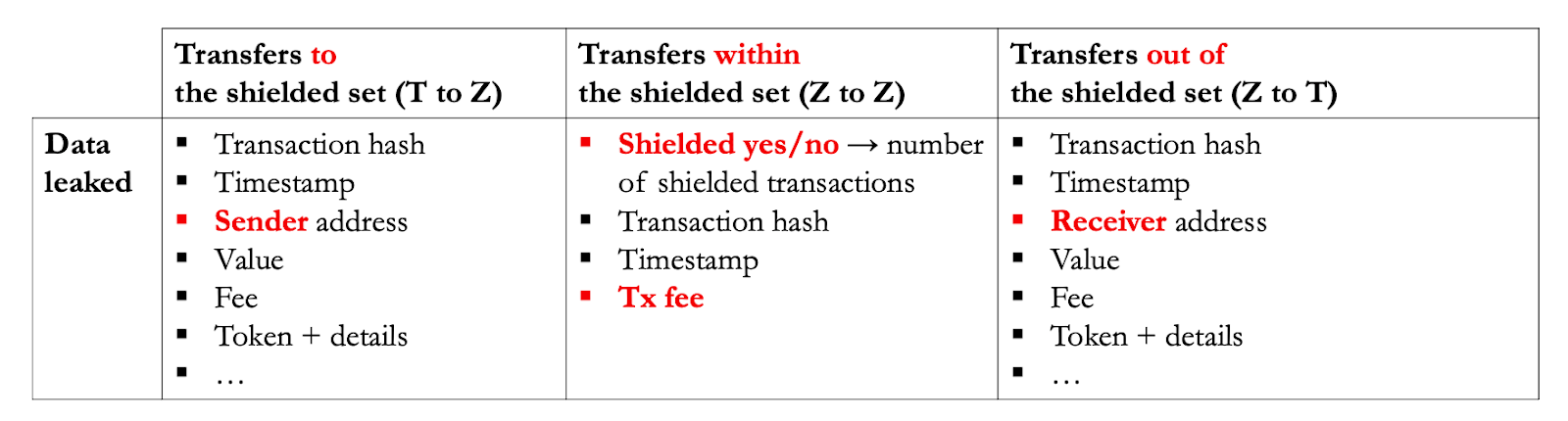

For a chain analyst, the transparent part is the same as any other pseudonymous blockchain (Bitcoin, Ethereum, etc). The shielded part can be trickier, because thanks to ZKPs, the interactions within the shielded pool do not reveal the transaction graph. But this does not mean that there is zero data being leaked.

What the hell is a shielded pool in Zcash? Don’t quote me on this, but think of it as interacting with a smart contract.

Say you have some ZEC in a transparent account (T) and you want to start using shielded transactions. The first step is to transfer your ZEC from your T account to your shielded account (Z). This transfer is not fully shielded! It’s true that the recipient’s address (Z) is not revealed, but everything else is the same as a transparent address.

The same applies to unshielding, so transactions out of the shielded set from Z to T, where the sender address (Z) is not revealed, but the receiver address is.

Z to Z transactions don’t reveal transaction graphs, but this is not equivalent to zero data being leaked: the timestamp or the transaction fee are observable, and you can infer some statistics e.g. the total number of shielded transactions.

Most of the data is leaked whenever a transparent address is involved, the least data is leaked when interactions remain within the shielded set.

Sometimes, there are other reasons why a user needs to unshield, for example, to move from one shielded set to an upgraded one. To do so, you’d need to unshield at least once and every time a T address is involved.

Just to show how much can be done with this data, you can refer to a paper published in 2020, which deanonymized with 95% coverage of deposits to and 87.5% coverage of all withdrawals from the shielded pool. This paper achieved an increased clustering rate of 9% compared to a previous study in 2018. Both studies combined passive, simple active methods, and a little bit of OSINT to deanonymize Zcash.

And these are the results from academic studies, this doesn’t account for the results of chain analysts that do it for profit, who are probably a lot better capitalized than PhD students and their supervisors, such as Chainalysis, who raised a total of USD 536M by end of 2022.

Shielded execution VMs vs. chain Analysts

Remember, ZKPs != data protection

You can deploy ZKPs to enable data protection, but you can also deploy ZKPs for other properties such as succinctness in verification.

For example, in systems like Polygon Hermez or Scroll, ZKPs are used to enable on-chain verification of state transitions that were computed off-chain. Usually, a zkEVM system aims to support specific opcodes to enable compatibility with specific ZK rollups. Another example of ZKPs not being used for privacy but rather for succinctness are ZK bridges (e.g. the bridge by Succinct Labs).

What are shielded execution VMs? Basically, Ethereum or an Ethereum-like architecture, where the computation happens off-chain but that you can verify on-chain that a specific execution trace and state transition is correct. ZKPs are commonly used for: data protection, as ZKPs remove the need for publishing the data on-chain; and succinctness in verification, calling the verifier on-chain.

I classify protocols that use ZEXE, veri-ZEXE, xyz-ZEXE as shielded execution VMs, for example Aleo and Espresso (at least before their recent pivot).

Blockchain with a shielded execution VM != better data protection for its users. It depends on many factors.

The key question is, which world do you live in?

- World A: Your blockchain is a silo, users are only interacting with assets and dApps created on your chain.

- World B: Your blockchain interoperates with others, users to interact with a mix of assets and dApps created on your chain, as well as assets coming from other chains, to use them with shielded dApps on your chain.

If your answer is A – I have a lot of questions for you, like why you’re building a silo in 2023 – but the good news is that the attack surface of chain analysts is a lot smaller. The bad news is that the attack surface is smaller because the complexity of the shielded applications you can build on this chain is very limited.

There’s a lot to unwrap here and I won’t go into details, but it boils down to one key limitation from how shielded execution VMs are architected: they’re not designed to handle state interactivity for counterparty discovery, which almost every dApp needs. This is really important for data protection because it affects what data you (the user) have to disclose to other users involved in a multi-user interaction.

In other words, on ZEXE-like VMs, the first thing to consider is that you might need to rewrite the logic of a dApp for it to work (you can’t c/p a solidity contract over and call it a day); the second thing is that you’ll only be able to build dApps where the users already know the end states (e.g. transfers).

If you want to dig deeper, I can recommend the talk on counterparty discovery and how Taiga (Anoma’s unified execution environment) overcomes the limitation.

Talk on Taiga: a dark forest of zero-knowledge programmability at Zcon3 in 2022

Cross-chain transactions vs. chain Analysts

Most people reading this would answer B, as most users in crypto are already multichain. The multichain user is also more and more used to the idea of cross-blockchain interactions using bridges or interoperability protocols like IBC.

Unfortunately, bridges and interoperability protocols suck for data protection.

Cross-chain transactions are pseudonymous. This means that a chain analyst will find the same amount of data (entire transaction graph) in a transaction between Chain A and B and a transaction within Ethereum. This is due to a design constraint that permissionless bridges and IBC have.

Let’s look at a few examples.

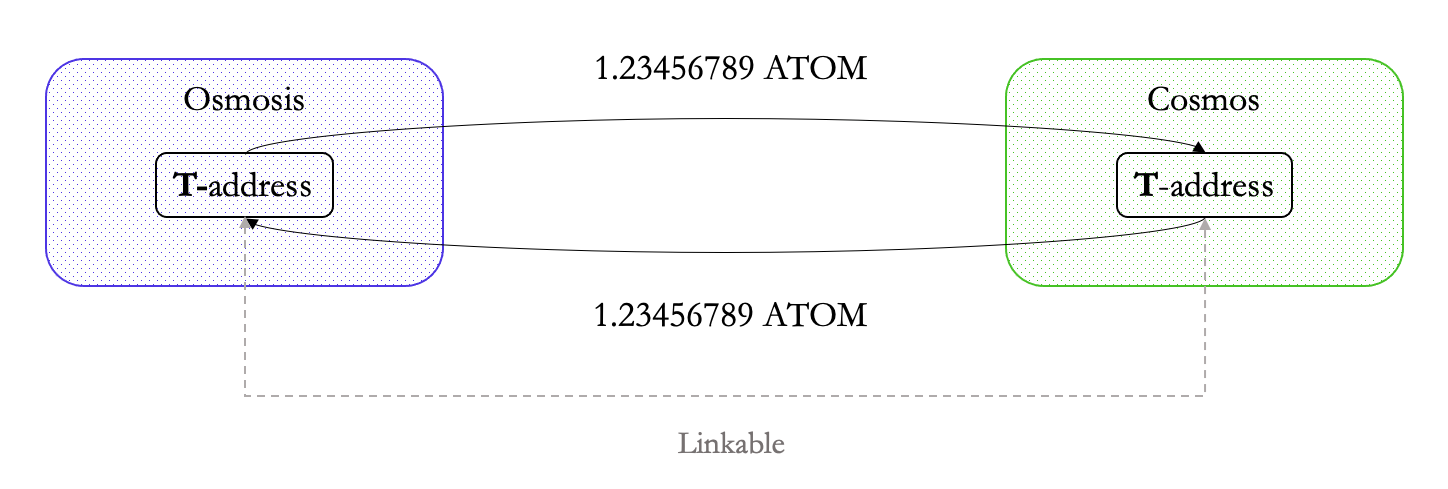

Here’s a transaction between Osmosis (transparent) and Cosmos (transparent) via IBC. As privacy is not natively supported by either chain, a chain analyst can observe as much data as they could in a Ethereum to Ethereum transaction:

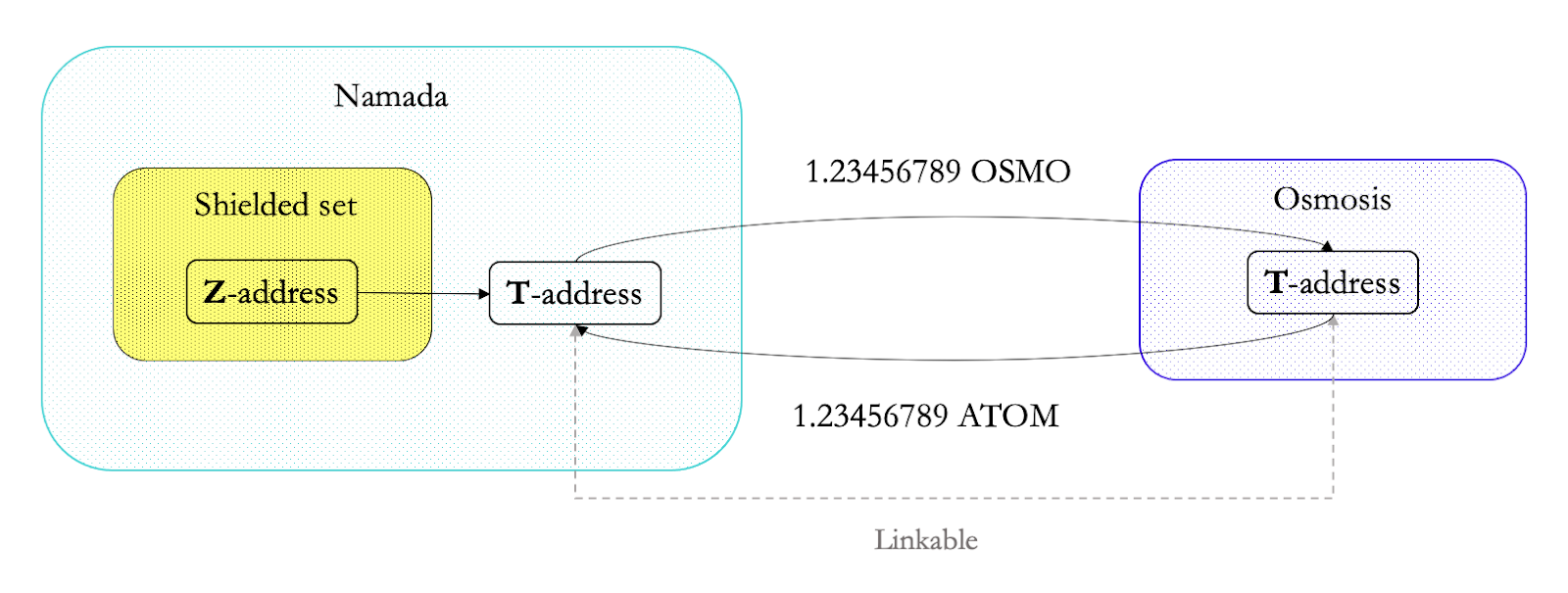

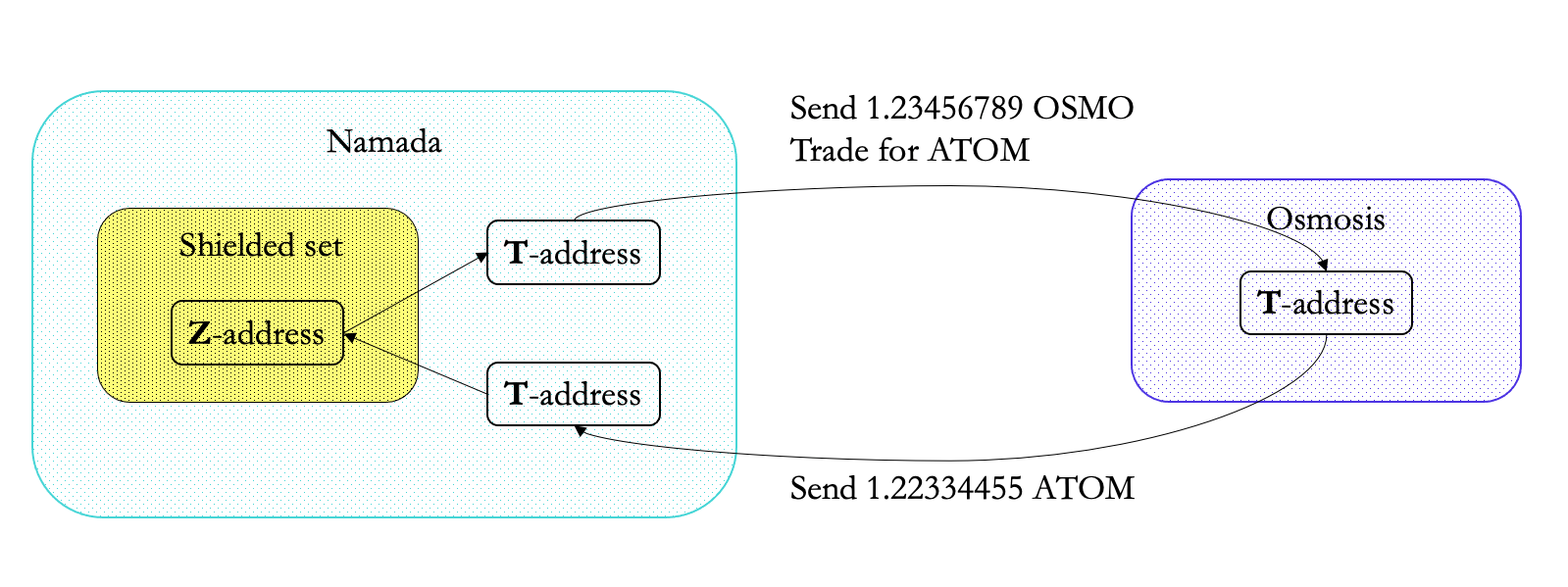

What about chains that do support shielding natively? E.g. Zcash, Namada, etc. Due to the design of IBC and any trustless bridging constructions (like the Namada <> Bridge), the transaction needs to be unshielded (from Z to T) before it can be transferred via IBC. As we’ve seen with Zcash before, the amount of data leaked is larger every time a transparent address is involved:

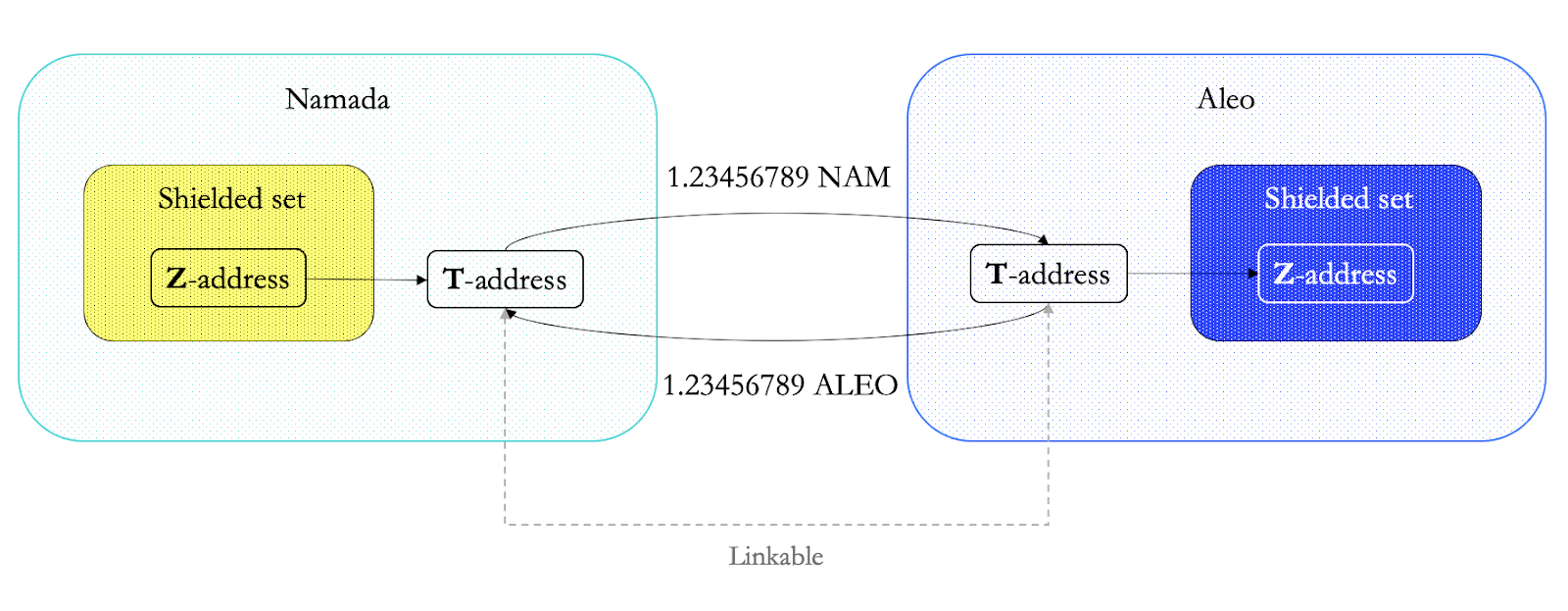

What about transactions between two chains with native shielding? Sadly, unless the bridge, interop protocol design changes, the requirement of unshielding remains the same, as you can see in the diagram below depicting a transaction between Namada and Aleo:

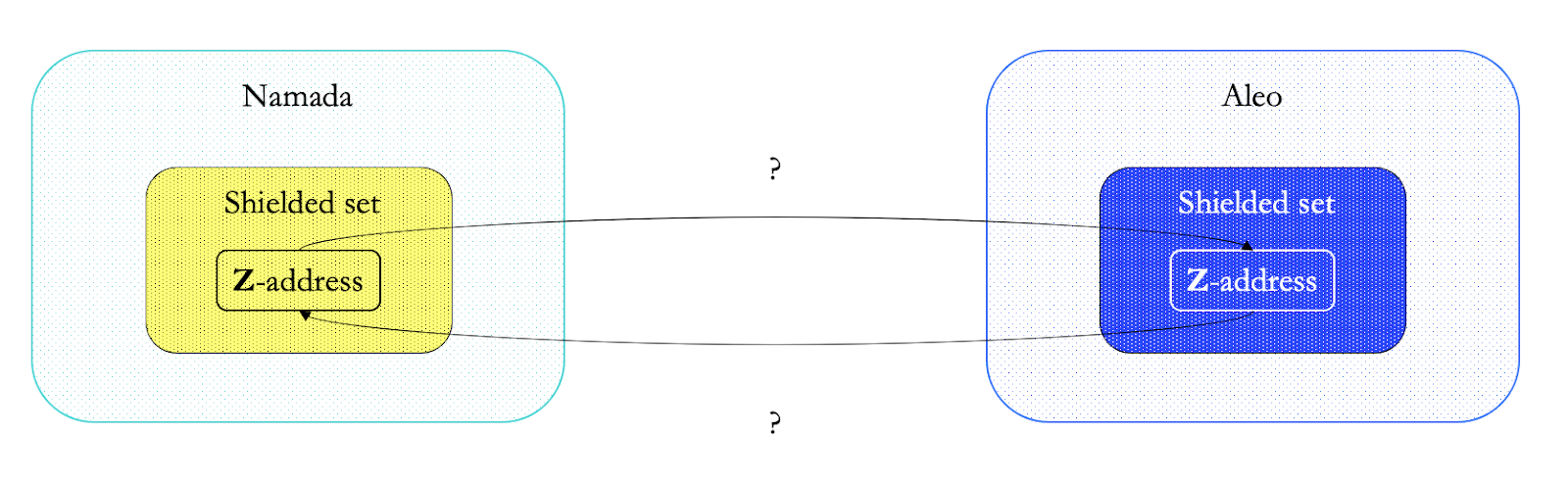

Luckily, this can be solved by changing the design of the interoperability and bridging protocols – and using shielded bridges instead.

Remember: the least data is leaked when interactions remain within the shielded set (aka Z to Z). The beauty of private bridges/IBC is that it removes the need to unshield for a cross-chain transfer, so even cross-chain transactions do not reveal a transaction graph:

TLDR; data protection tech sucks really hard for users and the lives of chain analysts is too ez.

So how do we turn the tables around?

Maximizing on-chain data protection

Wat do? If we want to offer the best data protection guarantees for multichain users today?

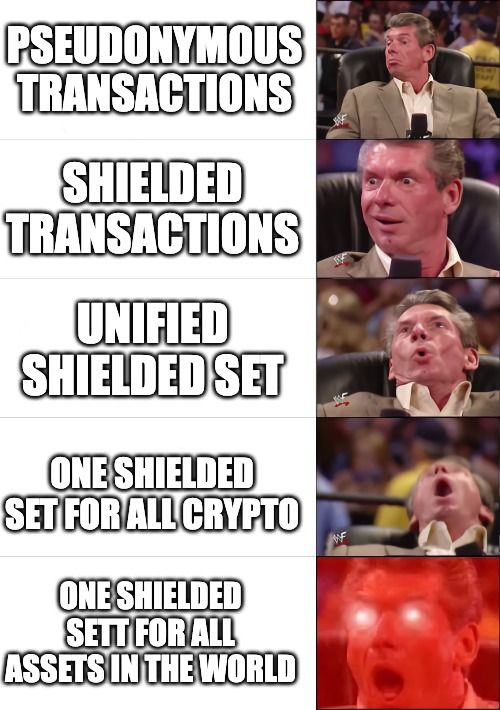

It’s very simple: shielded set size is all that matters.

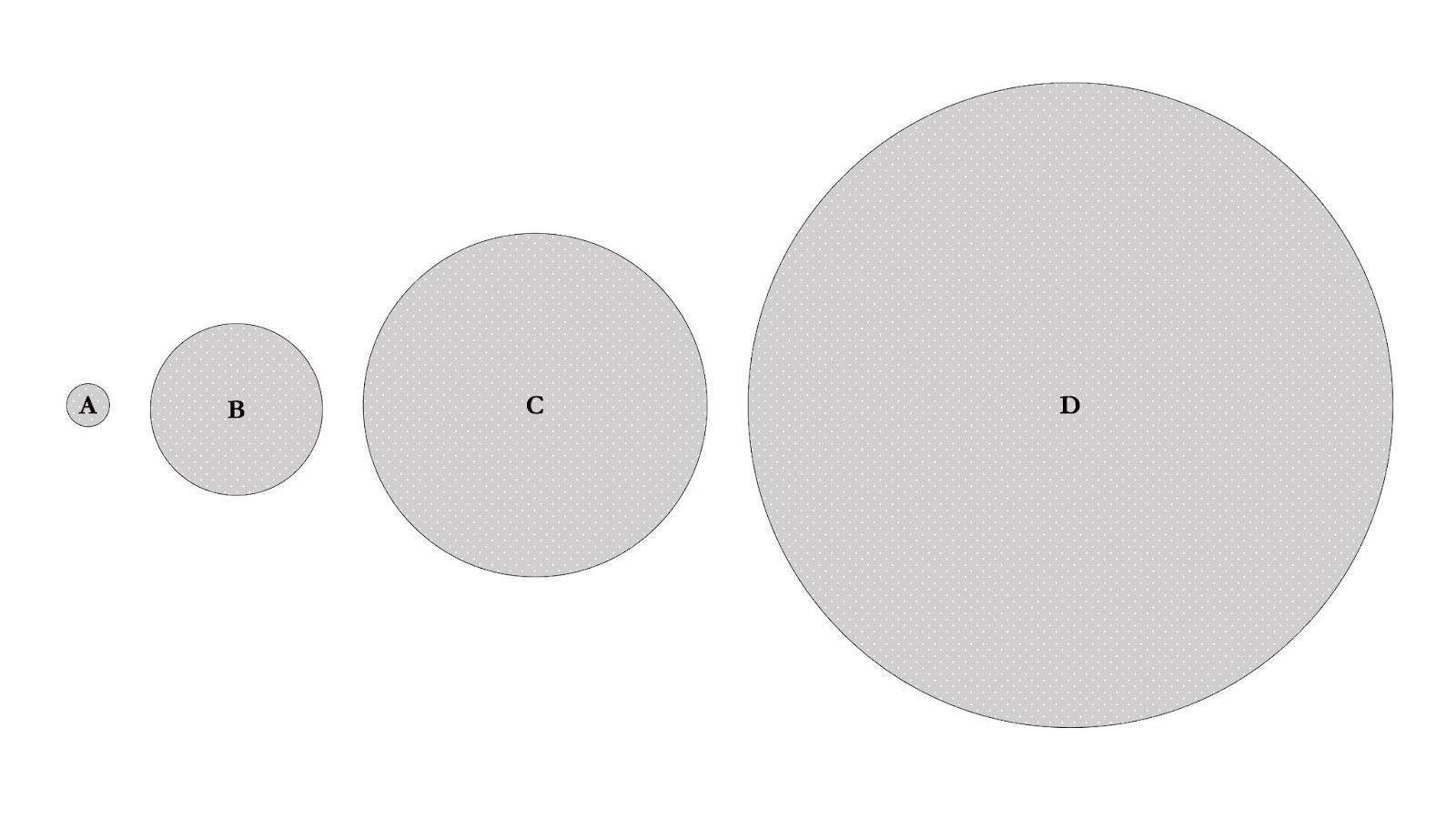

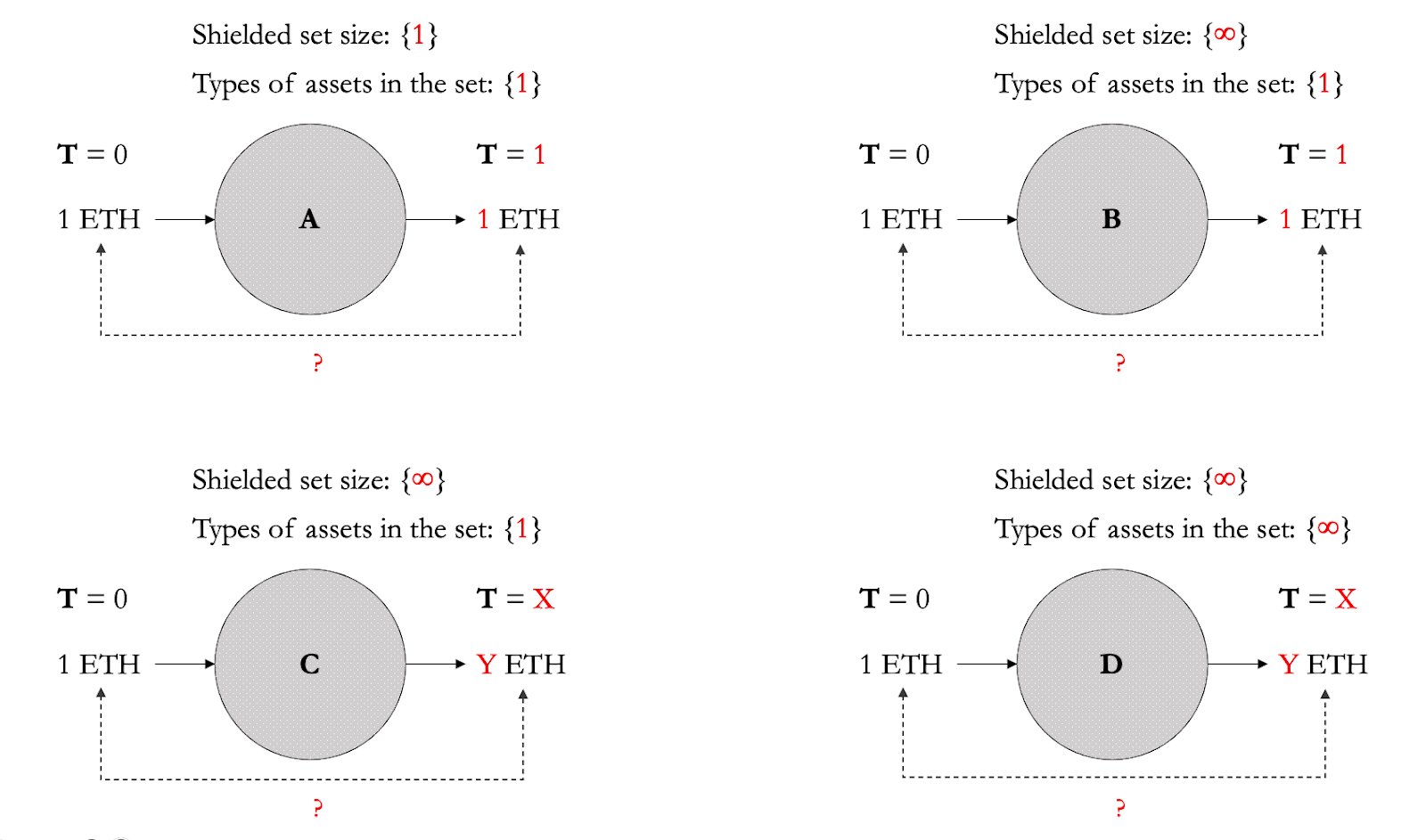

- Quick exercise: figure 11 shows 4 shielded sets (A-D), where the size of the shielded set measured by the number of shielded transactions and

A < B < C < D. - Question: which shielded set is the hardest to deanonymize?

We can definitely agree that shielded set A is significantly easier to deanonymize than D.

Providing the best on-chain data protection guarantees today is not rocket science.

All you need is two principles: first, grow the shielded set’s size infinitely – because the larger the size, the better the guarantees for each individual transaction; second, minimize the usage of transparent transactions and maximize the usage of shielded transactions – because the most of the data is leaked whenever a transparent address is involved, and the least data is leaked when interactions remain within the shielded set.

Growing the shielded set’s size infinitely

First, we need to remove what is limiting the size of the shielded set. The design of cryptocurrency protocols, privacy dApps, and shielded execution VMs which result in a fragmentation of shielded sets.

Another way to look at it is how the design directly limits the size of the shielded set: the limit of Zcash anonymity set is bound to the ZEC in circulation – and ZEC has the best anonymity sets known to us today. The theoretical limit of the anonymity size of the entire crypto would be all networks and assets, which is orders of magnitude larger than the individual asset anonymity set – this is why we need a unified shielded set for any assets no matter the type (read more on the MASP circuit). This can be combined with shielded bridges connecting all shielded sets to achieve an even larger shielded set. After all, privacy loves company, and so do blockchains.

But even if we were to turn all crypto into one shielded set, the size is still small compared to the size of the anonymity set of the USD. On the other hand, the anonymity set of fiat currencies is limited to the currency in itself, so what’s really powerful with the MASP is that if all fiat currencies were to be digitized, it could combine all crypto and fiat currencies’ anonymity set, which is not possible with web2 infrastructure.

Remaining in the shielded set

Remember, the least data is leaked when interactions remain within the shielded set. The first hurdle to overcome is to encourage everyone to use shielded transactions over transparent transactions and afterwards remain in the shielded set. This can be achieved by an economic mechanism which incentivises users to start using shielded transactions and to continue using them while effectively contributing to the shielded set’s size (read more about the mechanism and the CC circuit). Very important to note: assets in the shielded set are not locked and are usable freely within the shielded set – and there’s a surprising amount of applications that can be built solely on multi-asset shielded transactions. The more applications, the more shielded transactions, the larger the shielded set.

In addition, remove the need to leave the shielded set. This applies in cases where the user wants to use a feature or application that exists on another chain. This is what shielded actions are for: shielded accounts can sign a sequence of actions to e.g. use Osmosis without losing any privacy. This is even better with private bridges/IBC, as even the contents of the shielded actions would not be leaked.

Boosting data protection through UX

Even with shielded actions and/or shielded bridges/IBC, users might need to unshield their assets. To make the best protection accessible for everyone, the best end-user product needs to be vertically integrated with the protocol. At the interface level, on-chain shielding can be maximally optimized with features including: randomizing values and times, randomizing fees, and automatic creation of transparent addresses on the chain or destination chain.

To help with intuition, which of the transactions (to and from shielded sets A, B, C, and D) is the hardest for the chain analyst to link?

Conclusion

When it comes to shielded sets, go big or go home.

Future work

With this article I prioritize maximizing on-chain data protection guarantees. However, perfect on-chain shielding does not provide end-to-end guarantees. To achieve this, we’ll need to take into account all forms of OSINT, as well as data exposed by other layers in the architecture of blockchains like the P2P layer, mempool, data being read and not written.