Shielding Summit Recap

Shielding Summit was one of the truly unmissable events for 2024. Held on a peaceful island in the middle of Brussels’s Bois de la Cambre park, it was the place to be for privacy and data protection advocates escaping the hustle and bustle of EthCC. If you missed it and don’t have time to watch all the videos from the event, read on below for a recap of the most important takeaways.

Shielding Summit was a 1-day event held in Brussels during EthCC2024. Organized collaboratively by Heliax, Privacy Guardians, Web3Privacy Now, Knowable, and Shielded Labs, the event was dedicated to pushing the frontiers of privacy in Web3. Shielding Summit brought together the community of founders, builders, and policy advocates advancing the future of privacy, data protection, and public goods funding in decentralized systems, for a series of panels that touched key topics and trends for the space.

The day kicked off with an intro by Awa Sun Yin, cofounder of Anoma and Namada. She covered the vision for Shielding Summit as a collaborative space to bring the community together around privacy and public goods funding, as well as her motivations for joining the space, moving from ‘Game A’ to ‘Game B’, and the importance of data sovereignty.

Building and Funding Privacy as a Public Good

For the first panel of the day, Gavin Birch (Knowable), Althea Allen (Ethereum), Scott Moore (Gitcoin, Public Works), Meg Lister (Gitcoin), Mykola Siusko (Web3Privacy) and Lasha Antatze (Rarimo) discussed building and funding privacy as a public good.

How does privacy tech get funded?

In general there are three main categories: traditional investments and VC funding, grants, and crowdfunding or seed investments. VC investments are typically limited to cases where privacy has wide business applicability and investors can expect a large return on investment. With grants, there’s a tension between the types of projects that can be funded retroactively vs funded with initial grants.

A more recent alternative is inflationary funding, or using token issuance to fund things, for example with on-chain treasuries funded by inflation. Mykola urged caution around token based funding however, saying “I’ve seen so many teams destroyed by tokens, because instead of building things they’re over focused on a game that’s based on fear.” Of course, there’s a similar trap with VC funding, where there’s pressure to return value that can overwhelm the idealistic desire to build things in the right way, especially when people are there more for a quick return than for building something worthwhile that will last. Privacy maxis often forget, however, that VC funds are also imperative for backing research, funding conferences, and fueling technical innovation.

In each case, there’s a difficulty in measuring impact. While positive ROI is the goal of VC funding, grants can focus more on qualitative metrics that can be more suitable for public goods, with grant managers that can determine where the value is. Ultimately, if you’re doing privacy right, it should be difficult to get the typical success metrics, so projects should rely on conversations with their users, opt-in metrics etc.

One danger mentioned was the narrow focus in the space on Web3 public goods, forgetting that there’s an entire world of public goods outside of Web3 that we can tap into with, for example, human rights organizations. Many people have a strong interest in privacy rights, but as an industry we rely too heavily on technical jargon at the expense of making connections outside the space.

The narrative and conceptual side of privacy

Discussing the concept of privacy, a common theme was bringing the sorts of scenarios people are familiar with from daily life into the digital experience. For example, in the physical world you can go into a shop, walk around, buy something, and leave. Nobody needs to know your name, what you bought yesterday, nobody can make you engage in conversation, etc. Bringing this sort of anonymity to the digital world is difficult because all of the spaces are owned by someone who then becomes responsible for what happens there.

People need to understand that digital privacy is no different from the mundane freedoms people are used to in their everyday lives, like having a conversation with someone behind closed doors and knowing it isn’t being recorded. “The public blockchain is like outside. You don’t stand in the grocery store and plan your secret company financial stuff. You do that in your office,” Althea explained.

In the real world, we have public spaces and private spaces, open marketplaces and closed boardrooms. Without bringing these same abilities to the on-chain world, businesses, governments, and other types of organizations that require privacy will never really adopt the technology. “What discerning organization would ever use this technology if all their financial information is exposed to everyone: All their patterns, all their relationships. NGMI,” Gavin explained.

It’s not true that people don’t care about privacy, the panelists argued. It’s just that the term means something different to everyone, so it makes communication and marketing around privacy extremely difficult. Ultimately, Althea explained, privacy is a crucial part of the Web3 project: “This is the powerful value proposition for the combination of blockchains and public/private interfaces — that you can have coordination through a global, visible, reliable public ledger, while also maintaining your privacy, which is actually your humanity and agency.”

Bridging the gap between advocacy, policy, and tech

Next up, Adrian Brink (Anoma/Namada), Marina Markezic (EUCI), Alexis Roussel (NYM), Andreas Glarner (MME), Amit Chaudary (Labyrinth), and Fatemeh Fannizadeh (Heliax) discussed bridging the gap between advocacy, policy, and tech.

The current regulatory landscape

Painting an image of the current regulatory landscape around privacy was a big part of the discussion. While Swiss regulators are generally recognized as ahead of the curve (they understand the tech to the point you don’t even need to explain zero-knowledge to them, panelists mentioned), others at the EU level have also been catching up, having worked on MiCA since 2017. However, with changing EU parliamentary elections, some of the most knowledgeable regulators have left and so there’s a clean slate with new people to talk to.

Many of the bodies commonly referred to as regulators, for example FINMA in Switzerland, are not actually producing legislation but enforcing regulations based on their interpretations of the law. Because of this interpretive element, it’s imperative that industry leaders engage in conversation to help guide how those laws are enforced.

Ultimately, even if it means more companies standing up and going to court, it’s our role as an industry to challenge their thinking. The enforcement side is often more liberal than the legislation side, panelists explained, because the need to be confident that an enforcement action can be upheld in court.

Local vs global

So what are projects more focused on, local or global policymaking and regulation? First, of course, they aim to be compliant in their home country. Then, they look at where their users are. They then analyze which regulators are most likely to touch their business, and whether they need to exclude customers from places like the US.

Ultimately, there’s concern around a lack of global coordination. We had a G7 summit for AI, why don’t we have one for digital assets as well? Of course, in the realm of risk mitigation, nothing is certain. We live in the world of decentralization and it’s very different from the legal language we’re used to today, which is difficult to apply to decentralized networks. This leads to an uncertain environment for projects caught in the middle where regulations don’t apply well.

Andreas explained, “It’s a nice thought to think that we’ll have a harmonized regulator body making sure everything is running correctly, but let's be honest, the risk that this one agency gets it wrong is tremendously high. If you create such a big body they have their own internal dynamics. It’s not meant to do harm, but I prefer the distributed approach: let’s get twenty jurisdictions and let’s give it a try and maybe one of them gets it right. If we only have one try and we get it wrong then you’re in a mess.”

Panelists also pointed out the benefits that this technology can bring to the compliance landscape. The whole financial system is based around data acquisition, where you’re forced to create honeypots of data that are a risk both for consumers and the companies forced to collect and maintain that data.

With Web3, we can prove that we don’t need that data and that we can still protect users’ security. We’re getting to the point where we can reduce the cost of compliance to near zero with things like ZK tech. “The cost to collect and maintain the data of users is rising year by year with the data protection regime. I need to lower that cost and become more efficient, and ZK and other privacy technologies should allow me to do that,” Andreas explained.

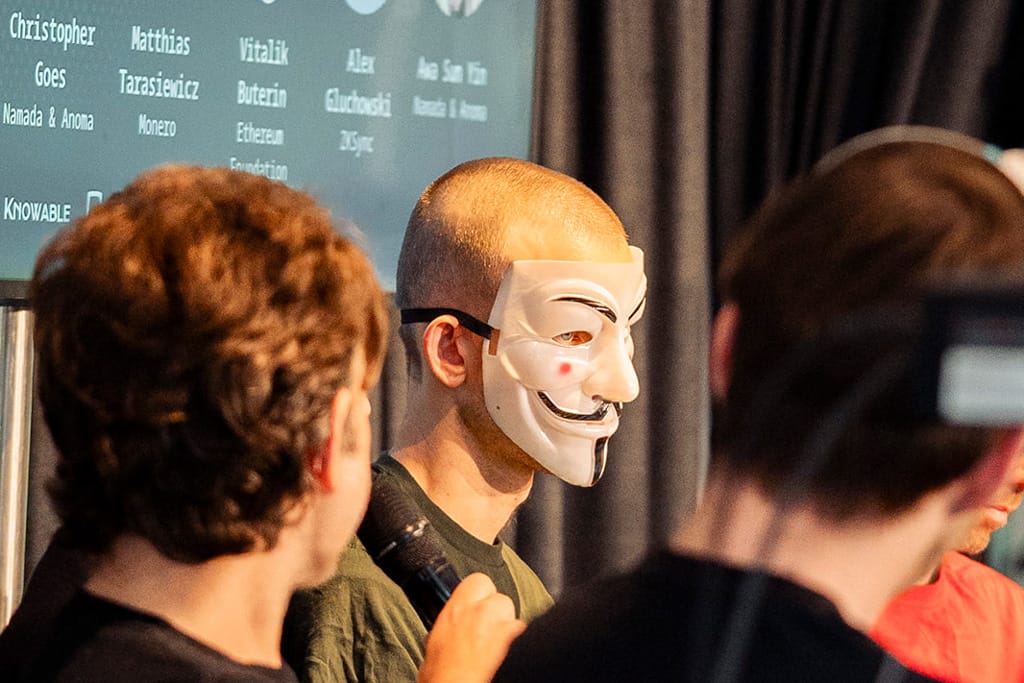

Vitalik Buterin, Zooko, Christopher Goes, Matthias Tarasiewicz & Alex G on the frontiers of privacy

Next we were joined by Vitalik Buterin (Ethereum), Zooko (zcash), Christopher Goes (Anoma/Namada), Matthias Tarasiewicz (Monero) & Alex G (ZKSync) for a discussion on the frontiers of privacy: the evolution of protocols, communities and ecosystems, moderated by Awa Sun Yin (Anoma/Namada).

The conversation covered a wide range of topics, from the very technical to more broad visionary topics. Vitalik started by sharing his thoughts on zk-STARKS as something historically used for scalability instead of privacy, but that has huge potential for privacy tech, particularly with off-chain use cases where STARKS faster proving time can provide benefits.

For the realm of interoperability, Alex argued, ZK proofs are the only real solution. But why should we care about interoperability? According to Christopher, in a world with multiple chains where you lose privacy each time you move between them, this introduces ways for adversaries to see what you’re doing and target you.

Panelists were asked what keeps them in the space and why they care about privacy. “I was born in a prison called the USSR,” Alex said. “I learned that freedom is the engine that drives prosperity…. There’s nothing more important or impactful than to work on something that increases freedom in the world.”

For Christopher: “To preserve the ability for communities to interoperate while at the same time maintaining autonomy. This to me is the promise this technology offers. At the moment most communities have to choose…. Forcing this choice on people is terrible and unnecessary.”“You can’t use a radically transparent thing like bitcoin for your business,” Zooko explained. “I realized that Zcash could be a mainstream thing that could help the rest of us.”

Vitalik’s answer got some laughter: “When I make some payments, a lot of the time people end up writing weird coin media articles about it. So instead I send payments into Railway, and instead people write weird coin media articles about how I send stuff into Railway…. I regularly get this visceral confirmation that this isn’t just abstract ideology, this is something that is actually valuable and important. And aside from that, the math is wicked awesome.”

Do people care about privacy?

Part of the reason it might seem like people don’t care about privacy is that we’ve failed to build interfaces that reflect what the technology actually does, Christopher argued:

“User interfaces lie to the user, whether consciously or not. When you open up Whatsapp on your phone, it appears that you’re sending a message to Zooko, but actually it should say recipients: Zooko, the CIA, and Whatsapp employees. We as technologists have failed to build interfaces that reflect what the technology actually does. The only way we can have a digital society where people understand the technology that they’re interacting with is if we find ways to design interfaces that use metaphors to present what that technology will do.”

“You always hear that young people don’t care about privacy,” Zooko said, “and then I found out that they care a lot. They’re very thoughtful about who they’re sharing with and what, and when. They care a great deal about privacy.”

For Christopher, people also need to demand technology where they can raise their expectations rather than lowering them: “people have gotten used to technology that doesn’t work in their best interest. They’ve gotten so used to it that they’ve given up on imagining an alternative world…. The US government used to fund open source technology research… A lot of what we’re working on today came out of public funding. Our democratic institutions have failed.”

Vitalik mentioned work being done in the Ethereum community on things like privacy pools, which enable separating out the bad actors from those using the technology for legitimate purposes.

Of course, Awa pointed out, on-chain privacy is the lowest hanging fruit, but what about the full stack? What about end-to-end privacy?Christopher argued that “sometimes crypto is not ambitious enough. If we’re going to build complex P2P layers and we have 10s or 100s of millions of dollar budgets, we might as well try to fix the TCP/IP stack, because it was a mistake; it was not designed with cryptographic identity in mind. If we rework it with the cryptographic tools we now have, we can provide a unified user experience almost like a super app that supports payments, chat, docs, etc, but is private and gives users autonomy and interoperability. If we can do that we’d blow all these existing companies out of the water.”

Is the word privacy a mistake?

Awa closed out the conversation by questioning the word privacy itself. Indeed, terms like information flow control more accurately reflect what the technology does, Vitalik pointed out.

For Christopher, “The word privacy is tarnished in the public eye and often conveys an act of hiding, which is not what’s going on in digital systems. What’s going on in digital systems is always an act of disclosing information. These technologies simply give users more freedom over what information to disclose.”

Zooko, who has been a champion of normalizing the word privacy (wearing a ‘Privacy is Normal’ shirt for the event), conceded that the term does have some baggage. Reiterating Christopher’s previous point about UX design, he argued:

“If Whatsapp showed that Mark Zuckerberg was one of the participants of all your chats, or if Telegram showed that Vladimir Putin was a participant in all your chats, you wouldn’t have to use the words privacy, non-privacy, confidentiality, anonymity. Good UX and high security is actually more compatible than incompatible.”

Building self-sovereign infrastructure and WW3 resilient societies

The final panel of the day featured Zachary Williamson (Aztec), Ameen Soleimani (Privacy Pools), Ryan Lackey (Evertas Insurance), Ian Miers (University of Maryland, Aleo) and Adrian Brink (Anoma/Namada) discussing building self-sovereign infrastructure and WW3 resilient societies, moderated by Michelle Lai (Electric Coin Co).

A good portion of the initial conversation centered around defining terms and getting on the same page about what scenarios we can/need to protect against. For Adrian, the key thing is that, during a global conflict in a multipolar world order, there’s a loss of coordination at the global level, with global communications systems and connectivity being among the first things to go.

So then, what does WW3 resistant tech look like? Michelle suggested it needs to give people the ability to not be singled out, through being able to do three main things privately: communicate, organize, and transact.

Building systems where the ability to abuse the data of users is minimized or eliminated is also key. As Ameen, Suggested: “Design your systems to be resilient against not only external actors but even potentially yourself because you don’t know if you’re going to be the good guy defending it in the future.” Centralized databases are not resilient and can be abused by adversaries and malicious actors.

“People need to think of having data around as like toxic waste and a liability, do not want to collect it in the first place, and be actively pushing back against regulations that require them to collect it,” Ryan argued.

Coordination and use of privacy preserving technologies gets difficult when you’re cut off from larger global systems. If the key to staying safe is not being singled out, you need to be wary of what the anonymity set of any privacy technology is. If you’re the only person using it, your privacy guarantees are not going to be enough. In any scenario where you can’t trust your local government, Adrian explained, transacting on any privacy system is going to be risky, especially if not many people are using it.

Being able to broadcast to broader global systems may be key here. If you can broadcast your transaction to a neutral place like Switzerland, in a way that doesn’t reveal your IP address, you can still access databases and compute there.

ZK was also discussed as a good solution for identity in a multipolar world, where people can attest to specific things without needing to reveal too much information. What you’d want is the ability to start from scratch and switch to a different system, not being forced into a single global system, Adrian argued.

To close out the day, Michelle asked the panelists if we’ve failed to achieve the original goals of the cypherpunk movement. It’s more complicated than that, panelists argued. The original aspirations may have gone unachieved because the web was corrupted so early on, and the movement became a bit of an echo chamber. But things go through cycles, and there’s a lot of potential that’s still in motion. “The history of the cypherpunk movement and cryptography in America actually still gives me hope that America will eventually get things right,” Ameen shared.

Let’s hope that these sorts of conversations continue to push the boundaries of privacy and data protection forward. Thank you to everyone who joined and made this one of the most impactful events of EthCC week, and to all the privacy builders out there, keep on building!